Napoleon Gives Up the Throne Again

| State of war of the Seventh Coalition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function of the Napoleonic Wars and the Coalition Wars | |||||||

| Click an image to load the boxing. Left to right, top to lesser: Battles of Quatre Bras, Ligny, Waterloo | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 800,000–i,000,000[1] | 280,000[i] | ||||||

The Hundred Days (French: les Cent-Jours IPA: [le sɑ̃ ʒuʁ]),[2] also known as the War of the 7th Coalition, marked the period between Napoleon'due south return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the 2d restoration of King Louis XVIII on viii July 1815 (a period of 110 days).[a] This menstruum saw the War of the Seventh Coalition, and includes the Waterloo Campaign,[three] the Neapolitan War as well as several other pocket-size campaigns. The phrase les Cent Jours (the hundred days) was showtime used by the prefect of Paris, Gaspard, comte de Chabrol, in his speech welcoming the king back to Paris on eight July.[b]

Napoleon returned while the Congress of Vienna was sitting. On 13March, 7 days before Napoleon reached Paris, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw, and on 25March Austria, Prussia, Russia and the United kingdom, the four Great Powers and key members of the 7th Coalition, leap themselves to put 150,000 men each into the field to stop his dominion.[six] This set the stage for the last disharmonize in the Napoleonic Wars, the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, the second restoration of the French kingdom, and the permanent exile of Napoleon to the afar island of Saint Helena, where he died in May 1821.

Background [edit]

Napoleon's rise and autumn [edit]

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars pitted France against diverse coalitions of other European nations most continuously from 1792 onward. The overthrow and subsequent public execution of Louis XVI in France had greatly disturbed other European leaders, who vowed to crush the French Republic. Rather than leading to France's defeat, the wars allowed the revolutionary regime to aggrandize across its borders and create customer republics. The success of the French forces made a hero out of their best commander, Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1799, Napoleon staged a successful coup d'état and became First Consul of the new French Consulate. Five years afterwards, he crowned himself Emperor Napoleon I.

The rising of Napoleon troubled the other European powers as much every bit the earlier revolutionary regime had. Despite the formation of new coalitions confronting him, Napoleon's forces connected to conquer much of Europe. The tide of war began to plough after a disastrous French invasion of Russia in 1812 that resulted in the loss of much of Napoleon's ground forces. The following year, during the State of war of the Sixth Coalition, Coalition forces defeated the French in the Battle of Leipzig.

Following its victory at Leipzig, the Coalition vowed to press on to Paris and depose Napoleon. In the last calendar week of February 1814, Prussian Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher advanced on Paris. After multiple attacks, manoeuvring, and reinforcements on both sides,[7] Blücher won the Boxing of Laon in early on March 1814; this victory prevented the coalition army from being pushed north out of France. The Battle of Reims went to Napoleon, but this victory was followed past successive defeats from increasingly overwhelming odds. Coalition forces entered Paris later the Battle of Montmartre on 30 March 1814.

On vi April 1814, Napoleon abdicated his throne, leading to the accession of Louis Eighteen and the beginning Bourbon Restoration a month later. The defeated Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba off the declension of Tuscany, while the victorious Coalition sought to redraw the map of Europe at the Congress of Vienna.

Exile in Elba [edit]

The journey of a modern hero, to the island of Elba. Print shows Napoleon seated backwards on a donkey on the road "to Elba" from Fontainebleau; he holds a cleaved sword in one manus and the ass's tail in the other while two drummers follow him playing a adieu(?) march.

Napoleon spent simply 9 months and 21 days in an uneasy forced retirement on Elba (1814–1815), watching events in France with corking interest as the Congress of Vienna gradually gathered.[eight] As he foresaw, the shrinkage of the smashing Empire into the realm of old French republic acquired intense dissatisfaction among the French, a feeling fed by stories of the tactless manner in which the Bourbon princes treated veterans of the Grande Armée and the returning royalist nobility treated the people at large. Equally threatening was the full general state of affairs in Europe, which had been stressed and wearied during the previous decades of near abiding warfare.[8]

The conflicting demands of major powers were for a fourth dimension so exorbitant equally to bring the Powers at the Congress of Vienna to the verge of war with each other.[9] Thus every chip of news reaching remote Elba looked favourable to Napoleon to retake power as he correctly reasoned the news of his render would cause a popular rising as he approached. He also reasoned that the render of French prisoners from Russia, Germany, U.k. and Spain would replenish him instantly with a trained, veteran and patriotic army far larger than that which had won renown in the years before 1814. So threatening were the symptoms, that the royalists at Paris and the plenipotentiaries at Vienna talked of deporting him to the Azores or to Saint Helena, while others hinted at bump-off.[viii] [ten]

Congress of Vienna [edit]

At the Congress of Vienna (November 1814 – June 1815) the various participating nations had very different and alien goals. Tsar Alexander of Russia had expected to absorb much of Poland and to leave a Polish boob state, the Duchy of Warsaw, as a buffer confronting further invasion from Europe. The renewed Prussian state demanded all of the Kingdom of Saxony. Austria wanted to allow neither of these things, while information technology expected to regain command of northern Italian republic. Castlereagh, of the United Kingdom, supported France (represented past Talleyrand) and Austria and was at variance with his own Parliament. This almost caused a war to break out, when the Tsar pointed out to Castlereagh that Russian federation had 450,000 men nearly Poland and Saxony and he was welcome to attempt to remove them. Indeed, Alexander stated "I shall be the Rex of Poland and the King of Prussia will be the King of Saxony".[eleven] Castlereagh approached King Frederick William Iii of Prussia to offer him British and Austrian support for Prussia'due south annexation of Saxony in render for Prussia's support of an contained Poland. The Prussian king repeated this offer in public, offending Alexander so deeply that he challenged Metternich of Austria to a duel. Only the intervention of the Austrian crown stopped it. A breach between the 4 Great Powers was avoided when members of Britain's Parliament sent word to the Russian administrator that Castlereagh had exceeded his authority, and U.k. would not support an independent Poland.[12] The matter left Prussia deeply suspicious of any British involvement.

Return to France [edit]

The brig Inconstant, under Helm Taillade and ferrying Napoleon to France, crosses the path of the brig Zéphir, under Captain Andrieux. Inconstant flies the tricolour of the Empire, while Zéphir flies the white ensign of the House of Bourbon.

While the Allies were distracted, Napoleon solved his problem in characteristic fashion. On 26 February 1815, when the British and French guard ships were absent, he slipped abroad from Portoferraio on lath the French brig Inconstant with some 1,000 men and landed at Golfe-Juan, betwixt Cannes and Antibes, on ane March 1815. Except in royalist Provence, he was warmly received.[8] He avoided much of Provence past taking a route through the Alps, marked today equally the Route Napoléon.[13]

Firing no shot in his defence, his troop numbers swelled until they became an army. On v March, the nominally royalist 5th Infantry Regiment at Grenoble went over to Napoleon en masse. The next 24-hour interval they were joined by the seventh Infantry Regiment under its colonel, Charles de la Bédoyère, who was executed for treason past the Bourbons later the campaign ended. An chestnut illustrates Napoleon'southward charisma: when royalist troops were deployed to end the march of Napoleon's force at Laffrey, near Grenoble, Napoleon stepped out in front of them, ripped open his glaze and said "If whatever of you will shoot his Emperor, here I am." The men joined his cause.[14]

Marshal Ney, at present ane of Louis Xviii's commanders, had said that Napoleon ought to be brought to Paris in an iron cage, but on xiv March, Ney joined Napoleon with 6,000 men. Five days later, later proceeding through the countryside promising constitutional reform and direct elections to an associates, to the acclaim of gathered crowds, Napoleon entered the capital, from where Louis XVIII had recently fled.[8]

The royalists did not pose a major threat: the duc d'Angoulême raised a small-scale forcefulness in the south, just at Valence it did not provide resistance against Imperialists under Grouchy's command;[viii] and the duke, on 9 April 1815, signed a convention whereby the royalists received a free pardon from the Emperor. The royalists of the Vendée moved later and caused more difficulty for the Imperialists.[8]

Napoleon'south health [edit]

The prove every bit to Napoleon's wellness is somewhat alien. Carnot, Pasquier, Lavalette, Thiébault and others idea him prematurely aged and enfeebled.[8] At Elba, equally Sir Neil Campbell noted, he became inactive and proportionately corpulent.[15] There, too, as in 1815, he began to suffer intermittently from retention of urine, but to no serious extent.[8] For much of his public life, Napoleon was troubled by hemorrhoids, which made sitting on a horse for long periods of fourth dimension difficult and painful. This condition had disastrous results at Waterloo; during the battle, his disability to sit on his horse for other than very brusque periods of time interfered with his ability to survey his troops in combat and thus exercise control.[16] Others saw no marked change in him; while Mollien, who knew the emperor well, attributed the lassitude which now and then came over him to a feeling of perplexity caused by his changed circumstances.[8]

Constitutional reform [edit]

At Lyon, on thirteen March 1815, Napoleon issued an edict dissolving the existing chambers and ordering the convocation of a national mass meeting, or Champ de Mai, for the purpose of modifying the constitution of the Napoleonic empire.[17] He reportedly told Benjamin Abiding, "I am growing former. The repose of a constitutional king may suit me. It will more than surely arrange my son".[8]

That piece of work was carried out by Benjamin Constant in concert with the Emperor. The resulting Acte additionel (supplementary to the constitutions of the Empire) bestowed on French republic a hereditary Chamber of Peers and a Chamber of Representatives elected by the "electoral colleges" of the empire.[8]

Co-ordinate to Chateaubriand, in reference to Louis Xviii's ramble lease, the new constitution—La Benjamine, it was dubbed—was only a "slightly improved" version of the charter associated with Louis XVIII's assistants;[8] however, afterwards historians, including Agatha Ramm, have pointed out that this constitution permitted the extension of the franchise and explicitly guaranteed press freedom.[17] In the Republican mode, the Constitution was put to the people of France in a plebiscite, but whether due to lack of enthusiasm, or considering the nation was suddenly thrown into war machine preparation, only ane,532,527 votes were cast, less than one-half of the vote in the plebiscites of the Consulat; however, the benefit of a "big majority" meant that Napoleon felt he had constitutional sanction.[8] [17]

Napoleon was with difficulty dissuaded from quashing the three June election of Jean Denis, comte Lanjuinais, the staunch liberal who had then often opposed the Emperor, as president of the Sleeping accommodation of Representatives. In his last advice to them, Napoleon warned them not to imitate the Greeks of the late Byzantine Empire, who engaged in subtle discussions when the ram was battering at their gates.[viii]

Military mobilisation [edit]

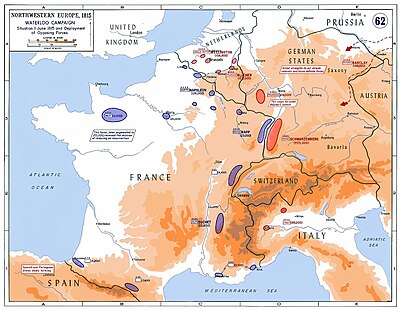

Strategic situation in Western Europe in 1815: 250,000 Frenchmen faced a coalition of near 850,000 soldiers on 4 fronts. In add-on, Napoleon had to leave 20,000 men in Western French republic to reduce a royalist insurrection.

During the Hundred Days both the Coalition nations and Napoleon mobilised for state of war. Upon re-supposition of the throne, Napoleon institute that Louis Xviii had left him with few resource. There were 56,000 soldiers, of which 46,000 were fix to campaign.[18] Past the cease of May the full military available to Napoleon had reached 198,000 with 66,000 more in depots training up but not yet ready for deployment.[xix] Past the end of May Napoleon had formed L'Armée du Nord (the "Army of the N") which, led past himself, would participate in the Waterloo Entrada.

For the defence of French republic, Napoleon deployed his remaining forces inside France with the intention of delaying his foreign enemies while he suppressed his domestic ones. By June he had organised his forces thus:

- Five Corps, – Fifty'Armée du Rhin – commanded by Rapp, cantoned nigh Strasbourg;[20]

- VII Corps – L'Armée des Alpes – allowable by Suchet,[21] cantoned at Lyon;

- I Corps of Ascertainment – Fifty'Armée du Jura – commanded by Lecourbe,[20] cantoned at Belfort;

- II Corps of Observation[22] – L'Armée du Var – commanded by Brune, based at Toulon;[23]

- III Corps of Observation[22] – Army of the Pyrenees orientales[24] – commanded by Decaen, based at Toulouse;

- IV Corps of Ascertainment[22] – Army of the Pyrenees occidentales[24] – allowable by Clauzel, based at Bordeaux;

- Army of the West,[22] – Armée de fifty'Ouest [24] (also known as the Army of the Vendee and the Army of the Loire) – commanded by Lamarque, was formed to suppress the Royalist coup in the Vendée region of French republic which remained loyal to King Louis XVIII during the Hundred Days.

The opposing Coalition forces were the post-obit:

Archduke Charles gathered Austrian and centrolineal High german states, while the Prince of Schwarzenberg formed another Austrian ground forces. King Ferdinand VII of Espana summoned British officers to atomic number 82 his troops against French republic. Tsar Alexander I of Russia mustered an army of 250,000 troops and sent these rolling toward the Rhine. Prussia mustered two armies. One under Blücher took mail service alongside Wellington's British army and its allies. The other was the North German Corps nether Full general Kleist.[25]

- Assessed as an firsthand threat by Napoleon:

- Anglo-centrolineal, commanded by Wellington, cantoned south-west of Brussels, headquartered at Brussels.

- Prussian Army commanded by Blücher, cantoned south-east of Brussels, headquartered at Namur.

- Close to the borders of French republic but assessed to be less of a threat past Napoleon:

- The German language Corps (Northward High german Federal Regular army) which was part of Blücher's army, simply was acting independently south of the main Prussian regular army. Blücher summoned information technology to join the main army in one case Napoleon's intentions became known.

- The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine, commanded by Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg.

- The Swiss Army, commanded by Niklaus Franz von Bachmann.

- The Austrian Army of Upper Italian republic – Austro-Sardinian Army – commanded by Johann Maria Philipp Frimont.

- The Austrian Army of Naples, commanded by Frederick Bianchi, Duke of Casalanza.

- Other coalition forces which were either converging on France, mobilised to defend the homelands, or in the process of mobilisation included:

- A Russian Army, allowable by Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly, marching towards France

- A Reserve Russian Army to support Barclay de Tolly if required.

- A Reserve Prussian Ground forces stationed at home in guild to defend its borders.

- An Anglo-Sicilian Ground forces under General Sir Hudson Lowe, which was to be landed by the Royal Navy on the southern French declension.

- Two Castilian Armies were assembling and planning to invade over the Pyrenees.

- A Netherlands Corps, under Prince Frederick of kingdom of the netherlands, was not nowadays at Waterloo but every bit a corps in Wellington'south ground forces it did take part in minor military actions during the Coalition's invasion of French republic.

- A Danish contingent known as the Majestic Danish Auxiliary Corps (commanded by Full general Prince Frederik of Hesse) and a Hanseatic contingent (from the gratis cities of Bremen, Lübeck and Hamburg) later commanded by the British Colonel Sir Neil Campbell, were on their way to bring together Wellington;[26] both however, joined the ground forces in July having missed the conflict.[27] [28]

- A Portuguese contingent, which due to the speed of events never assembled.

War begins [edit]

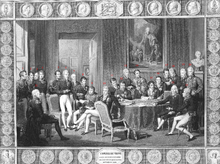

Plenipotentiaries at the Congress of Vienna

At the Congress of Vienna, the Smashing Powers of Europe (Austria, Great Great britain, Prussia and Russia) and their allies declared Napoleon an outlaw,[29] and with the signing of this annunciation on 13 March 1815, so began the War of the 7th Coalition. The hopes of peace that Napoleon had entertained were gone – war was at present inevitable.

A further treaty (the Treaty of Alliance against Napoleon) was ratified on 25 March, in which each of the Corking European Powers agreed to pledge 150,000 men for the coming disharmonize.[thirty] Such a number was not possible for Great United kingdom, as her standing army was smaller than those of her three peers.[31] Besides, her forces were scattered effectually the globe, with many units still in Canada, where the War of 1812 had recently concluded.[32] With this in mind, she made up her numerical deficiencies by paying subsidies to the other Powers and to the other states of Europe who would contribute contingents.[31]

Some fourth dimension after the allies began mobilising, information technology was agreed that the planned invasion of French republic was to commence on 1 July 1815,[33] much later than both Blücher and Wellington would take liked, equally both their armies were ready in June, alee of the Austrians and Russians; the latter were even so some altitude away.[34] The advantage of this afterwards invasion engagement was that it immune all the invading Coalition armies a take chances to be prepare at the same time. They could deploy their combined, numerically superior forces against Napoleon'south smaller, thinly spread forces, thus ensuring his defeat and avoiding a possible defeat within the borders of French republic. Even so this postponed invasion appointment allowed Napoleon more time to strengthen his forces and defences, which would make defeating him harder and more than costly in lives, time and money.

Napoleon now had to make up one's mind whether to fight a defensive or offensive entrada.[35] Defence would entail repeating the 1814 campaign in France, but with much larger numbers of troops at his disposal. French republic'southward master cities (Paris and Lyon) would exist fortified and ii cracking French armies, the larger before Paris and the smaller earlier Lyon, would protect them; francs-tireurs would be encouraged, giving the Coalition armies their own taste of guerrilla warfare.[36]

Napoleon chose to set on, which entailed a pre-emptive strike at his enemies earlier they were all fully assembled and able to co-operate. By destroying some of the major Coalition armies, Napoleon believed he would then be able to bring the governments of the Seventh Coalition to the peace table[36] to discuss terms favourable to himself: namely, peace for France, with himself remaining in ability as its head. If peace were rejected past the Coalition powers, despite any pre-emptive military machine success he might take achieved using the offensive war machine choice available to him, and so the war would keep and he could turn his attention to defeating the rest of the Coalition armies.

Napoleon's decision to attack in Belgium was supported by several considerations. Outset, he had learned that the British and Prussian armies were widely dispersed and might be defeated in detail.[37] Further, the British troops in Belgium were largely second-line troops; nearly of the veterans of the Peninsular War had been sent to America to fight the War of 1812.[38] And, politically, a French victory might trigger a friendly revolution in French-speaking Brussels.[37]

Waterloo Campaign [edit]

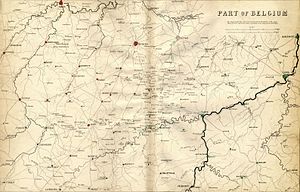

A portion of Belgium with some places marked in colour to indicate the initial deployments of the armies but before the offset of hostilities on 15 June 1815, with British forces in red, Prussians in green, and French in blue

The Waterloo Campaign (15 June – 8 July 1815) was fought between the French Army of the Due north and two Seventh Coalition armies: an Anglo-allied army and a Prussian army. Initially the French ground forces was allowable past Napoleon Bonaparte, but he left for Paris subsequently the French defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. Command then rested on Marshals Soult and Grouchy, who were in turn replaced by Marshal Davout, who took control at the request of the French Provisional Regime. The Anglo-allied army was commanded past the Duke of Wellington and the Prussian army by Prince Blücher.

Commencement of hostilities (15 June) [edit]

Hostilities started on fifteen June when the French drove in the Prussian outposts and crossed the Sambre at Charleroi and secured Napoleon's favoured "primal position"—at the junction between the cantonment areas of Wellington's ground forces (to the west) and Blücher's regular army to the east.[39]

Battles of Quatre Bras and Ligny (xvi June) [edit]

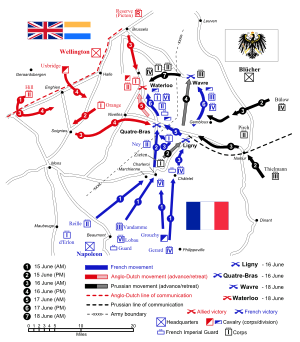

Map of the Waterloo entrada

On 16 June, the French prevailed, with Marshal Ney commanding the left wing of the French army holding Wellington at the Battle of Quatre Bras and Napoleon defeating Blücher at the Battle of Ligny.[40]

Interlude (17 June) [edit]

On 17 June, Napoleon left Grouchy with the right wing of the French army to pursue the Prussians, while he took the reserves and command of the left wing of the ground forces to pursue Wellington towards Brussels. On the dark of 17 June, the Anglo-allied army turned and prepared for battle on a gentle escarpment, nigh 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the village of Waterloo.[41]

Boxing of Waterloo (xviii June) [edit]

The adjacent day, the Battle of Waterloo proved to be the decisive battle of the campaign. The Anglo-allied army stood fast against repeated French attacks, until with the aid of several Prussian corps that arrived on the due east of the battlefield in the early evening, they managed to rout the French Army.[42] Grouchy, with the right fly of the army, engaged a Prussian rearguard at the simultaneous battle of Wavre, and although he won a tactical victory, his failure to forbid the Prussians marching to Waterloo meant that his actions contributed to the French defeat at Waterloo. The adjacent day (xix June), Grouchy left Wavre and started a long retreat back to Paris.[43]

Invasion of France [edit]

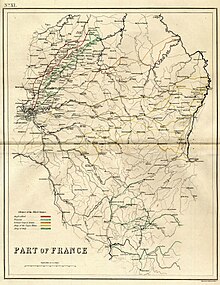

Invasion of France by the Seventh Coalition armies in 1815

After the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon chose non to remain with the army and endeavor to rally it, only render to Paris to effort to secure political support for further action. This he failed to do and was forced to resign. The two Coalition armies hotly pursued the French regular army to the gates of Paris, during which time the French, on occasion, turned and fought some delaying actions, in which thousands of men were killed.[44]

Abdication of Napoleon (22 June) [edit]

On arriving at Paris, three days after Waterloo, Napoleon still clung to the hope of concerted national resistance, merely the atmosphere of the chambers and of the public mostly forbade whatsoever such attempt. Napoleon and his brother Lucien Bonaparte were almost alone in believing that, by dissolving the chambers and declaring Napoleon dictator, they could salve France from the armies of the powers at present converging on Paris. Even Davout, government minister of state of war, advised Napoleon that the destiny of France rested solely with the chambers. Clearly, information technology was time to safeguard what remained, and that could best be done under Talleyrand'south shield of legitimacy.[45] Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès was the minister of justice during this time and was a close confidant of Napoleon.[46]

Napoleon himself at last recognised the truth. When Lucien pressed him to "dare", he replied, "Alas, I have dared only as well much already". On 22 June 1815 he abdicated in favour of his son, Napoleon Francis Joseph Charles Bonaparte, well knowing that information technology was a formality, as his four-yr-sometime son was in Austria.[47]

French Provisional Government [edit]

With the abdication of Napoleon, a conditional government with Joseph Fouché as acting president was formed.

Initially, the remnants of the French Army of the Due north (the left wing and the reserves) that was routed at Waterloo were commanded by Marshal Soult, while Grouchy kept command of the right wing that had fought at Wavre. However, on 25 June, Soult was relieved of his command by the Provisional Government and was replaced by Grouchy, who in turn was placed nether the command of Marshal Davout.[48]

On the same day, 25 June, Napoleon received from Fouché, the president of the newly appointed provisional government (and Napoleon'due south erstwhile police chief), an intimation that he must go out Paris. He retired to Malmaison, the quondam home of Joséphine, where she had died presently subsequently his first abdication.[47]

On 29 June, the near approach of the Prussians, who had orders to seize Napoleon, dead or alive, caused him to retire westwards toward Rochefort, whence he hoped to attain the United states.[47] The presence of blockading Royal Navy warships under Vice Admiral Henry Hotham, with orders to prevent his escape, forestalled this plan.[49]

Coalition forces enter Paris (vii July) [edit]

French troops concentrated in Paris had as many soldiers as the invaders and more cannons.[ citation needed ] There were two major skirmishes and a few minor ones well-nigh Paris during the commencement few days of July. In the get-go major skirmish, the Battle of Rocquencourt, on i July, French dragoons, supported by infantry and allowable by General Exelmans, destroyed a Prussian brigade of hussars under the command of Colonel von Sohr (who was severely wounded and taken prisoner during the skirmish), before retreating.[fifty] In the second skirmish, on iii July, General Dominique Vandamme (under Davout's control) was decisively defeated past Full general Graf von Zieten (nether Blücher's command) at the Battle of Issy, forcing the French to retreat into Paris.[51]

With this defeat, all hope of holding Paris faded and the French Provisional Authorities authorised delegates to accept capitulation terms, which led to the Convention of St. Cloud (the give up of Paris) and the end of hostilities between France and the armies of Blücher and Wellington.[52]

On iv July, nether the terms of the Convention of St. Deject, the French army, commanded by Align Davout, left Paris and proceeded to cross the river Loire. The Anglo-allied troops occupied Saint-Denis, Saint Ouen, Clichy and Neuilly. On five July, the Anglo-allied ground forces took possession of Montmartre.[53] On 6 July, the Anglo-centrolineal troops occupied the Barriers of Paris, on the right of the Seine, while the Prussians occupied those upon the left banking concern.[53]

On 7 July, the two Coalition armies, with Graf von Zieten's Prussian I Corps as the vanguard,[54] entered Paris. The Chamber of Peers, having received from the Provisional Regime a notification of the class of events, terminated its sittings; the Bedroom of Representatives protested, but in vain. Their President (Lanjuinais) resigned his Chair, and on the following solar day, the doors were closed and the approaches guarded by Coalition troops.[53] [55]

Restoration of Louis Xviii (viii July) [edit]

On viii July, the French King, Louis Eighteen, fabricated his public entry into Paris, amidst the acclamations of the people, and once more occupied the throne.[53]

During Louis XVIII's entry into Paris, Count Chabrol, prefect of the department of the Seine, accompanied by the municipal body, addressed the Male monarch, in the proper noun of his companions, in a spoken language that began "Sire,—1 hundred days have passed away since your majesty, forced to tear yourself from your dear affections, left your capital amidst tears and public consternation. ...".[5]

Give up of Napoleon (xv July) [edit]

Napoleon on Board the Bellerophon, exhibited in 1880 by Sir William Quiller Orchardson. Orchardson depicts the morning of 23 July 1815, equally Napoleon watches the French shoreline recede.

Unable to remain in France or escape from it, Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of HMSBellerophon in the early forenoon of xv July 1815 and was transported to England. Napoleon was exiled to the island of Saint Helena where he died in May 1821.[56] [47]

Other campaigns and wars [edit]

While Napoleon had assessed that the Coalition forces in and around Brussels on the borders of north-e France posed the greatest threat, considering Tolly's Russian army of 150,000 were nevertheless not in the theatre, Spain was slow to mobilise, Prince Schwarzenberg's Austrian army of 210,000 were deadening to cross the Rhine, and another Austrian force menacing the due south-eastern frontier of French republic was yet not a direct threat, Napoleon still had to place some badly needed forces in positions where they could defend France confronting other Coalition forces whatever the outcome of the Waterloo campaign.[57] [20]

Neapolitan State of war [edit]

The Neapolitan War betwixt the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples and the Austrian Empire started on 15 March 1815 when Marshal Joachim Murat declared state of war on Austria, and ended on 20 May 1815 with the signing of the Treaty of Casalanza.[58]

Napoleon had made his brother-in-constabulary, Joachim Murat, King of Naples on 1 August 1808. After Napoleon'southward defeat in 1813, Murat reached an agreement with Austria to relieve his ain throne. However, he realized that the European Powers, coming together as the Congress of Vienna, planned to remove him and return Naples to its Bourbon rulers. So, after issuing the and so-called Rimini Proclamation urging Italian patriots to fight for independence, Murat moved north to fight confronting the Austrians, who were the greatest threat to his dominion.[ commendation needed ]

The war was triggered by a pro-Napoleon uprising in Naples, after which Murat declared war on Republic of austria on 15 March 1815, five days before Napoleon's return to Paris. The Austrians were prepared for war. Their suspicions were aroused weeks earlier, when Murat applied for permission to march through Austrian territory to set on the southward of France. Austria had reinforced her armies in Lombardy under the command of Bellegarde prior to state of war being declared.[ citation needed ]

The war ended after a decisive Austrian victory at the Battle of Tolentino. Ferdinand Four was reinstated equally King of Naples. Ferdinand then sent Neapolitan troops nether Full general Onasco to help the Austrian army in Italy attack southern France. In the long term, the intervention past Austria caused resentment in Italy, which further spurred on the drive towards Italian unification.[59] [lx] [61]

Civil war [edit]

Provence and Brittany, which were known to incorporate many royalist sympathisers, did not rise in open revolt, merely La Vendée did. The Vendée Royalists successfully took Bressuire and Cholet, before they were defeated past General Lamarque at the Battle of Rocheserviere on 20 June. They signed the Treaty of Cholet 6 days later on 26 June.[21] [63]

Austrian campaign [edit]

Rhine frontier [edit]

In early on June, General Rapp'southward Ground forces of the Rhine of near 23,000 men, with a leavening of experienced troops, advanced towards Germersheim to cake Schwarzenberg'southward expected accelerate, simply on hearing the news of the French defeat at Waterloo, Rapp withdrew towards Strasbourg turning on 28 June to check the 40,000 men of General Württemberg's Austrian III Corps at the battle of La Suffel—the last pitched boxing of the Napoleonic Wars and a French victory. The next day Rapp connected to retreat to Strasbourg and as well sent a garrison to defend Colmar. He and his men took no further active part in the campaign and eventually submitted to the Bourbons.[20] [64]

To the north of Württenberg'due south III Corps, General Wrede'due south Austrian (Bavarian) Iv Corps likewise crossed the French frontier, and so swung south and captured Nancy, against some local popular resistance on 27 June. Attached to his control was a Russian disengagement, nether the command of General Count Lambert, that was charged with keeping Wrede's lines of communication open. In early July, Schwarzenberg, having received a request from Wellington and Blücher, ordered Wrede to act as the Austrian vanguard and advance on Paris, and by 5 July, the main body of Wrede'south IV Corps had reached Châlons. On half-dozen July, the accelerate guard made contact with the Prussians, and on vii July Wrede received intelligence of the Paris Convention and a request to move to the Loire. By 10 July, Wrede's headquarters were at Ferté-sous-Jouarre and his corps positioned between the Seine and the Marne.[21] [65]

Further southward, General Colloredo's Austrian I Corps was hindered by General Lecourbe'due south Armée du Jura, which was largely made upwardly of National Guardsmen and other reserves. Lecourbe fought iv delaying actions between xxx June and 8 July at Foussemagne, Bourogne, Chèvremont and Bavilliers before like-minded to an ceasefire on 11 July. Archduke Ferdinand's Reserve Corps, together with Hohenzollern-Hechingen's II Corps, laid siege to the fortresses of Hüningen and Mühlhausen, with two Swiss brigades[66] [ page needed ] from the Swiss Regular army of General Niklaus Franz von Bachmann, aiding with the siege of Huningen. Like other Austrian forces, these likewise were pestered by francs-tireurs.[21] [67]

Italian frontier [edit]

Like Rapp farther north, Marshal Suchet, with the Armée des Alpes, took the initiative and on xiv June invaded Savoy. Facing him was Full general Frimont, with an Austro-Sardinian army of 75,000 men based in Italy. Withal, on hearing of the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, Suchet negotiated an armistice and roughshod back to Lyons, where on 12 July he surrendered the metropolis to Frimont'south army.[68]

The coast of Liguria was dedicated past French forces nether Marshal Brune, who savage dorsum slowly into the fortress city of Toulon, after retreating from Marseilles before the Austrian Army of Naples nether the command of Full general Bianchi, the Anglo-Sicilian forces of Sir Hudson Lowe, supported by the British Mediterranean fleet of Lord Exmouth, and the Sardinian forces of the Sardinian General d'Osasco, the forces of the latter being fatigued from the garrison of Squeamish. Brune did not surrender the urban center and its naval arsenal until 31 July.[21] [69]

Russian campaign [edit]

The chief body of the Russian Regular army, commanded by Field Marshal Count Tolly and amounting to 167,950 men, crossed the Rhine at Mannheim on 25 June—afterwards Napoleon had abdicated for the second fourth dimension—and although there was calorie-free resistance around Mannheim, it was over by the time the vanguard had advanced as far as Landau. The greater portion of Tolly's army reached Paris and its vicinity past the eye of July.[21] [seventy]

Treaty of Paris [edit]

All the participants of the War of the Seventh Coalition. Blue: The Coalition and their colonies and allies. Green: The First French Empire, its protectorates, colonies and allies.

Issy was the concluding field appointment of the Hundred Days. At that place was a campaign against fortresses still commanded by Bonapartist governors that concluded with the capitulation of Longwy on 13 September 1815. The Treaty of Paris was signed on xx November 1815, bringing the Napoleonic Wars to a formal terminate.

Under the 1815 Paris treaty, the previous year's Treaty of Paris and the Last Deed of the Congress of Vienna, of 9 June 1815, were confirmed. French republic was reduced to its 1790 boundaries; it lost the territorial gains of the Revolutionary armies in 1790–1792, which the previous Paris treaty had immune France to keep. France was at present besides ordered to pay 700 1000000 francs in indemnities, in five yearly installments,[c] and to maintain at its own expense a Coalition army of occupation of 150,000 soldiers[71] in the eastern border territories of French republic, from the English Channel to the edge with Switzerland, for a maximum of five years.[d] The ii-fold purpose of the military occupation was made clear past the convention annexed to the treaty, outlining the incremental terms by which France would issue negotiable bonds covering the indemnity: in add-on to safeguarding the neighbouring states from a revival of revolution in French republic, information technology guaranteed fulfilment of the treaty'southward financial clauses.[e]

On the same day, in a carve up document, U.k., Russia, Austria and Prussia renewed the Quadruple Alliance. The princes and gratuitous towns who were not signatories were invited to accede to its terms,[74] whereby the treaty became a part of the public police force according to which Europe, with the exception of the Ottoman Empire,[f] established "relations from which a system of existent and permanent balance of power in Europe is to be derived".[g]

See likewise [edit]

- Malplaquet annunciation issued to French by Wellington on 22 June 1815

- List of Napoleonic battles

Notes [edit]

- ^ Histories differ over the start and end dates of the Hundred Days; another popular period is from 1March, when Napoleon I landed in France, to his defeat at Waterloo on 18June.

- ^ Louis Eighteen fled Paris on 19March.[4] When he entered Paris on 8 July, Count Chabrol, prefect of the section of the Seine, accompanied by the municipal body, addressed Louis XVIII in the name of his companions, in a speech that began "Sire,—One hundred days have passed away since your majesty, forced to tear yourself from your dearest affections, left you majuscule amidst tears and public consternation. ...".[5]

- ^ Article 4 of the Definitive Treaty of 20 November 1815. The 1814 treaty had required only that French republic honour some public and private debts incurred by the Napoleonic government (Nicolle 1953, pp. 343–354), see Articles 18, nineteen and xx of the 1814 Paris Peace Treaty

- ^ The army of occupation and the Duke of Wellington's moderating transformation from soldier to statesman are discussed by Thomas Dwight Veve.[72]

- ^ A point made by Nicolle.[73]

- ^ Turkey, which had been excluded from the Congress of Vienna by the express wish of Russia (Strupp 1960–1962, "Wiener Kongress").

- ^ The quote is from Article I of the Boosted, Dissever, and Secret Articles to the [Paris Peace Treaty] of 30th May, 1814 (Hertslet 1875, p. 18); it is quoted to back up the sentence past Wood 1943, p. 263 and note 6 (Forest's main subject is the Treaty of Paris (1856), terminating the Crimean War).

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b Chandler 1966, p. 1015.

- ^ "Hundred Days". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved xi October 2021.

- ^ Beck 1911, "Waterloo Entrada".

- ^ Townsend 1862, p. 355.

- ^ a b Gifford 1817, p. 1511.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1996, p. 59.

- ^ Uffindell 2003, pp. 198, 200.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h i j k l g n o Rose 1911, p. 209.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1996, pp. 44, 45.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1996, p. 43.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1996, p. 48.

- ^ Adams 2011.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1996, p. 42.

- ^ Campbell, Northward., & Maclachlan, A. Northward. C. (1869). Napoleon at Fontainebleau and Elba: Being a periodical of occurrences in 1814-1815. London: J. Murray

- ^ Hibbert 1998, pp. 143, 144.

- ^ a b c Ramm 1984, pp. 132–134.

- ^ Chesney 1868, p. 34.

- ^ Chesney 1868, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Chandler 1981, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d east f Chandler 1981, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d Chalfont 1979, p. 205.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 775, 779.

- ^ a b c Chandler 1981, p. 30.

- ^ Chesney 1868, p. 36.

- ^ Plotho 1818, pp. 34, 35 (Appendix).

- ^ Hofschroer 2006, pp. 82, 83.

- ^ Sørensen 1871, pp. 360–367.

- ^ Baines 1818, p. 433.

- ^ Barbero 2006, p. two.

- ^ a b Glover 1973, p. 178.

- ^ Chartrand 1998, pp. ix, x.

- ^ Houssaye 2005, p. 327.

- ^ Houssaye 2005, p. 53.

- ^ Chandler 1981, p. 25.

- ^ a b Houssaye 2005, pp. 54–56.

- ^ a b Chandler 1966, p. 1016.

- ^ Chandler 1966, p. 1093.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 111–128.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 129–258.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 159–323.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 324–596.

- ^ Siborne 1848, p. 625.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 597–754.

- ^ Rose 1911, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Muel, Leon (1891). Gouvernements, ministères et constitutions de la France depuis cent ans. Marchal et Billard. p. 100. ISBN978-1249015024.

- ^ a b c d Rose 1911, p. 210.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 687, 717.

- ^ Cordingly 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 741–745.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 752–757.

- ^ Siborne 1848, pp. 754–756.

- ^ a b c d Siborne 1848, p. 757.

- ^ Lipscombe 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Waln 1825, pp. 482–483.

- ^ Laughton 1893, p. 354.

- ^ Beck 1911, p. 371.

- ^ Domenico Spadoni. "CASALANZA, Convenzione di". Archive. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Pietro Colletta (1858). History of the kingdom of Naples: 1734-1825, chapter III. T. Constable and Co.

- ^ "The annual register, or, a view of the history, politicks, and literature for the year. Volume 57 (A new edition), 1815 - chapter Vii". Archive. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ A Glance at Revolutionized Italy a Visit to Messina and a Tour Through the Kingdom of Naples ... in the Summer of 1848 by Charles Mac Farlane. Smith, Elderberry and C. 1849. pp. 33–.

- ^ Multiple Authors (17 September 2013). Revolutionary Wars 1775–c.1815. Amber Books Ltd. pp. 190–. ISBN978-1-78274-123-seven.

- ^ Gildea 2008, pp. 112, 113.

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 772.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 768–771.

- ^ Chapuisat 1921, Edouard Table Iii.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 773, 774.

- ^ Siborne 1895, pp. 775–779.

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 779.

- ^ Siborne 1895, p. 774.

- ^ Article v of the Definitive Treaty of xx November 1815.

- ^ Veve 1992, pp. nine, four, 114, 120.

- ^ Nicolle 1953, p. 344.

- ^ Final Act of the Congress of Vienna, Article 119.

Sources [edit]

- Adams, Keith (November 2011). "Driven: Citroen SM". Archetype and Operation Cars—Octane. Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013.

- Baines, Edward (1818). History of the Wars of the French Revolution, from the breaking out of the wars in 1792, to, the restoration of general peace in 1815 (in 2 volumes). Vol. ii. Longman, Rees, Orme and Brown. p. 433.

- Barbero, Alessandro (2006). The Boxing: a new history of Waterloo . Walker & Company. ISBN978-0-8027-1453-four.

- Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Macmillan.

- Chandler, David (1981) [1980]. Waterloo: The Hundred Days. Osprey Publishing.

- Chalfont, Lord; et al. (1979). Waterloo: Battle of Three Armies. Sidgwick and Jackson.

- Chapuisat, Édouard (1921). Der Weg zur Neutralität und Unabhängigkeit 1814 und 1815. Bern: Oberkriegskommissariat. (also published as: Vers la neutralité et fifty'indépendance. La Suisse en 1814 et 1815, Berne: Commissariat key des guerres)

- Chartrand, Rene (1998). British Forces in North America 1793–1815. Osprey Publishing.

- Chesney, Charles Cornwallis (1868). Waterloo Lectures: a study of the Campaign of 1815. London: Longmans Greenish and Co.

- Cordingly, David (2013). Billy Ruffian. A&C Black. p. vii. ISBN978-1-4088-4674-2.

- Gildea, Robert (2008). Children of the Revolution: The French, 1799–1914 (reprint ed.). Penguin Great britain. pp. 112, 113. ISBN978-0141918525.

- Gifford, H. (1817). History of the Wars Occasioned past the French Revolution: From the Kickoff of Hostilities in 1792, to the End of ... 1816; Embracing a Complete History of the Revolution, with Biographical Sketches of Most of the Public Characters of Europe. Vol. two. W. Lewis. p. 1511.

- Glover, Michael (1973). Wellington equally Armed forces Commander. London: Sphere Books.

- Hamilton-Williams, David (1996). Waterloo New Perspectives: the Neat Battle Reappraised. Wiley. ISBN978-0-471-05225-8.

- Hertslet, Edward, Sir (1875). The map of Europe by treaty; showing the various political and territorial changes which have taken place since the full general peace of 1814. London: Butterworths. p. 18.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1998). Waterloo (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Wordsworth Editions. p. 144. ISBN978-one-85326-687-4.

- Hofschroer, Peter (2006). 1815 The Waterloo Campaign: Wellington, his German allies and the Battles of Ligny and Quatre Bras. Vol. 1. Greenhill Books.

- Houssaye, Henri (2005). Napoleon and the Campaign of 1815: Waterloo. Naval & Military Press Ltd.

- Laughton, John Knox (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 353–355.

- Lipscombe, Nick (2014). Waterloo – The Decisive Victory. Osprey Publishing. p. 32. ISBN978-1-4728-0104-3.

- Nicolle, André (December 1953). "The Problem of Reparations after the Hundred Days". The Journal of Modern History. 25 (four): 343–354. doi:10.1086/237635. S2CID 145101376.

- Plotho, Carl von (1818). Der Krieg des verbündeten Europa gegen Frankreich im Jahre 1815. Berlin: Karl Friedrich Umelang.

- Ramm, Agatha (1984). Europe in the Nineteenth Century. London: Longman.

- Siborne, William (1848). The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 (4th ed.). Westminster: A. Constable.

- Siborne, William (1895). "Supplement section". The Waterloo Campaign 1815 (4th ed.). Birmingham, 34 Wheeleys Road. pp. 767–780.

- Sørensen, Carl (1871). Kampen om Norge i Aarene 1813 og 1814. Vol. 2. Kjøbenhavn.

- Stephens, Henry Morse (1886). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. viii. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 389–390.

- Strupp, G.; et al. (1960–1962). "Wiener Kongress". Wörterbuch des Völkerrechts (in German). Berlin. [ total citation needed ]

- Townsend, George Henry (1862). The Manual of Dates: A Lexicon of Reference to All the Most Important Events in the History of Mankind to be Found in Authentic Records. Routledge, Warne, & Routledge. p. 355.

- Uffindell, Andrew (2003). Groovy Generals of the Napoleonic Wars. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN978-1-86227-177-7.

- Veve, Thomas Dwight (1992). The Duke of Wellington and the British Army of Occupation in France, 1815–1818 (illustrated ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. ix, 4, 114, 120. ISBN978-0313279416.

- Waln, Robert (1825). Life of the Marquis de La Fayette: Major General in the Service of the U.s.a., in the War of the Revolution... J.P. Ayres. pp. 482–483.

- Woloch, Isser (2002). Napoleon and His Collaborators. W.Westward. Norton & Company. ISBN978-0-393-32341-two.

- Wood, Hugh McKinnon (April 1943). "The Treaty of Paris and Turkey's Status in International Law". The American Periodical of International Police. 37 (two): 262–274. doi:ten.2307/2192416. JSTOR 2192416.

Attribution [edit]

Further reading [edit]

- Abbot, John South.C. (1902). "Chapter XI: Life in Exile, 1815–1832". Makers of History: Joseph Bonaparte. New York and London: Harper & Brothers. pp. 320–324.

- Alexander, Robert Southward. (1991). Bonapartism and Revolutionary Tradition in France: The Federes of 1815. Cambridge University Press.

- Bowden, Scott (1983). Armies at Waterloo: a detailed analysis of the armies that fought history'southward greatest Battle. Empire Games Press. ISBN978-0-913037-02-7.

- Gurwood, Lt. Colonel (1838). The Dispatches of Field Marshal the Knuckles of Wellington. Vol. 12. J. Murray.

- Hofschroer, Peter (1999). 1815 The Waterloo Campaign: The German victory, from Waterloo to the autumn of Napoleon. Vol. ii. Greenhill Books. ISBN978-1-85367-368-9.

- Mackenzie, Norman (1984). The Escape from Elba. Oxford University Press.

- Lucas, F.Fifty. (1965). "'Long Lives the Emperor', an essay on The Hundred Days". The Historical Periodical. viii (one): 126–135. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00026868. JSTOR 3020309.

- Schom, Alan (1992). 1 Hundred Days: Napoleon's road to Waterloo. New York: Atheneum. pp. 19, 152.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Information Book. London: Greenhill Books.

- Wellesley, Arthur (1862). Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington. Vol. 10. London: United Services, John Murray.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hundred_Days

Post a Comment for "Napoleon Gives Up the Throne Again"